Experience the tranquil beauty and unique customs of Japanese temples and shrines. Discover the rituals, cultural significance, and etiquette for visiting these sacred sites.

While traveling in Japan, you’ll undoubtedly come across countless shrines and temples of all designs and sizes. In December 2019, The Agency for Cultural Affairs reported approximately 84,000 Shinto shrines and 77,000 temples throughout Japan.

These all play an important role in Japan’s history and culture, so it can be pretty daunting to determine the differences and how to pay respect to each one, especially if you have not grown up in Japan and aren’t familiar with the Japanese religious background. To make things a little more complicated, shrines and temples have different etiquette!

In this post, we want to guide you through everything you need to know about shrines and temples: their differences, a step-by-step guide to visiting them, and everything in between. First, we must look at the difference between Buddhism and Shintoism.

Buddhism and Shintoism

In contemporary Japan, there are two major religions: Buddhism and Shintoism.

Buddhism originated in India in the 6th century and was later brought to Japan via China and Korea. It involves the teachings of the Buddha, Gautama Siddhartha. There are various sects within the religion, including Shingon Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, and perhaps the most famous Zen Buddhism. Temples are where monks live, practice, and learn about Buddhism.

They can be distinguished by their name, usually corresponding to tera, -deraor -ji in Japanese. For example, Senso-ji in Asakusa and Todai-ji in Nara are just two of the most famous temples in Japan.

Shintoism predated Buddhism in Japan and translates to “Way of the gods.” It states that gods, or we in Japanese, are present in Shinrabansho (everything in the universe), with eight million residing in the form of mountains, rivers, trees, etc. – While there is no actual number, the figure eight represents infinity. Shrines are structures that have enshrined these kami and sometimes influential figures such as emperors or shogun (military leaders).

Shrines can be distinguished by their names, which typically end in jinja, jingu, or -sha in Japanese – for example, Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari Taisha and Tokyo’s Meiji-Jingu.

What is the Difference Between a Shrine and a Temple

Shrines and Temples can be defined by their appearance.

A temple’s entrance is marked by a large gate known as a sanmon. Typically, you’ll find statues of Nio (muscular guardians of the Buddha) flanked on either side. Moving inside the temple, you have the don’t knowwhere objects of worship are enshrined, and the monk’s living quarters. In the garan, you can find images and statues of the Buddha, where you can worship.

A pagoda and the kondo (main hall) are located nearby, where most of the temple’s treasures are located.

Another distinguishing feature of temples is the architecture. Typically, they will have tiled roofs with an ornament(s) on top.

A shrine’s entrance is marked by a torii gate, typically painted red but can also come in various colors and materials. The torii gate is said to separate the human world and sacred ground.

On the approach to the shrine, you will often find stone statues of everything (lion-like guardians) with a temizuya or chozuya (water basin) to purify yourself on the side. Further inside is the dogs (main sanctuary), where the enshrined deity resides. Unlike temples, these deities are often hidden and not in plain sight.

Shrines favor using natural materials such as wood and sometimes have thatched roofs, with chigi (distinctive forked finials) and katsuogi (crossbars).

Who Works at Shrines and Temples?

As we mentioned, people working at temples are called monks or obosanwho give sutras and perform teachings preached by the Buddha.

The people who work at shrines are known as shinshoku or kannushiwho perform rituals, company duties, and prayers. You might also find some miko (shrine maidens) who assist in the shrine grounds and performances.

Japanese Shrine Etiquette Tips

Shrine and temple etiquette vary slightly, so it is important to know the correct etiquette for each one.

- Upon reaching the torii gate entrance, slightly bow.

- Enter to the left or right of the center of the torii gate.

- Walk along the edge on the approach to the shrine.

- Head to the temizuya or chozuya to purify yourself. Here is a picture board of how to purify yourself.

- Pick up the ladle with your right hand and fill it with water. Wash your left hand.

- Then wash your right hand.

- Using your right hand, scoop some water and place it in your left hand. Rinse mouth.

- Wash your left hand again.

- Then, with both hands, raise the ladle and pour a small amount of water over it. (Check the photo below).

- At the main shrine, you will find an offering box. Put/throw a 5 yen coin in and ring the bell if the shrine has one. 5 yen is considered the lucky coin. However, a 1 or 10 yen coin is perfectly acceptable.

- Bow twice.

- Clap twice.

- With your hands together, make your prayer.

- After finishing your prayer, bow once more.

- When you leave the shrine, at the torii gate, turn around to the main hall and bow.

Japanese Temple Etiquette Tips

- At the sanmon entrance gate, bow slightly with your hands together. Step over the threshold of the gate.

- If the temple has one, head temizuya and purify yourself with the same method as the shrine.

- Purchase an incense.

- Light it with the designated lighter.

- Place in the incense burner and bow. Some people use their hands to spread the smoke over the body in wishes for good health and skin. Furthermore, do not use other people’s incense to burn yours, as it is said you will carry their sins.

- Go to the main hall and gently toss the coin into the offering box.

- If there is one, ring the bell two or three times.

- Bow slightly with your hands together and make your prayer. Do not clap.

- After finishing your prayer, bow again.

- When you leave the temple, at the sanmon, turn around to the main hall and bow.

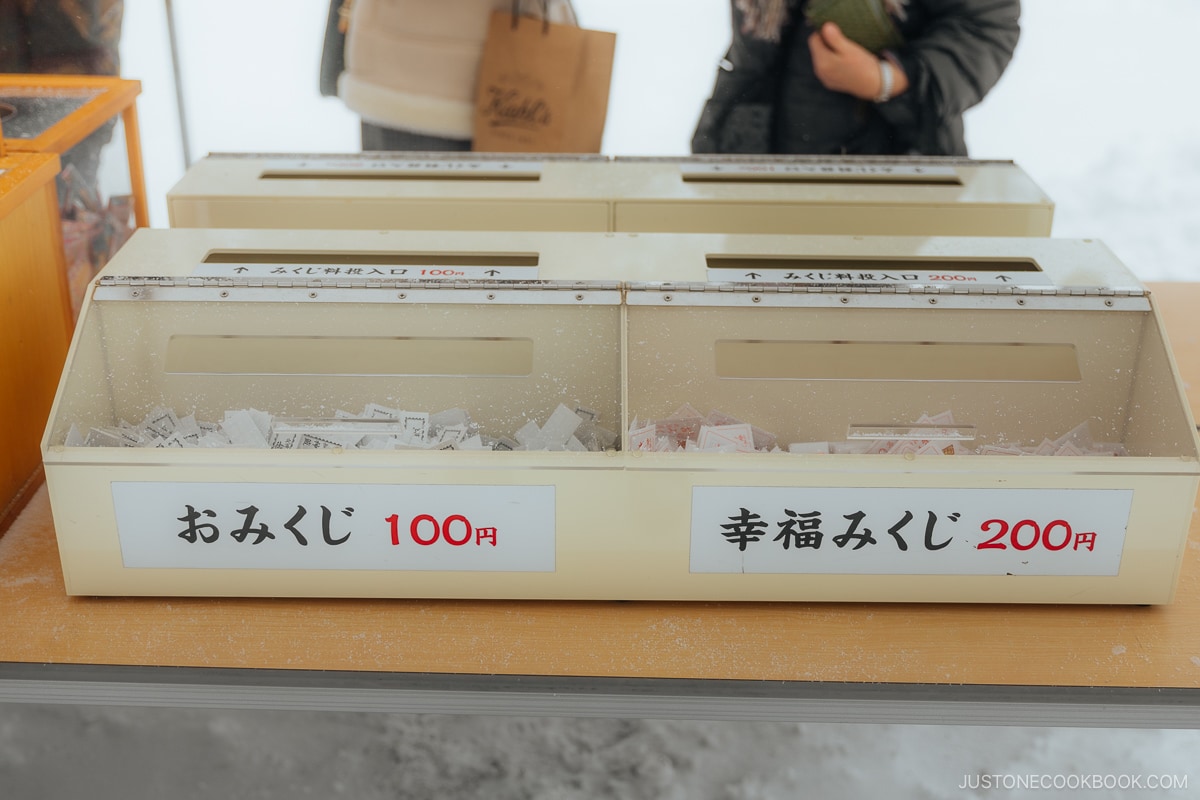

What is Omikuji

After praying at a temple or shrine, you can pick up an omikuji (fortune paper) at one of the nearby stalls for 100 to 200 yen. Depending on the shrine or temple, there are different ways of picking your omikuji.

In some places, you can shake a tube until a stick with a number on the tip comes out. Then, you pick the omikuji in the drawer with your number.

Some other places are more straightforward, as you randomly take your omikuji out of a box.

Also known as a “message from god,” Omikuji tells you whether you have good or bad luck and more minor details such as money, health, relationships, and more. There are different types of fortune, which we will list below:

- Daikichi – Great Fortune

- Chukichi – Medium Blessing

- Shokichi – Small Blessing

- Kichi – Blessing

- Hankichi – Half Blessing

- Hankyoshi (Sueyoshi) – Blessing to Come

- Suetsukichi (Suetsukichi) – Half Blessing to come

- Koshi (bad) – Misfortune

- Daikoshi (Great Misfortune) – Great misfortune

Japanese people usually pick up their omikuji at the start of the year during hatsumode to receive their fortune for the year. However, feel free to pick yours up whenever you are visiting!

Many people take their omikuji home, especially if it is good luck, and keep it in their wallet or purse. However, if you get a bad fortune, it is tradition to tie it to a pine tree. “Pine” (matsu in Japanese) sounds the same as the verb “to wait” (matsu), so the idea is that the fortune will wait at the tree instead of following you home. There may not be a pine tree in some places, but there is a dedicated rack to tie your omikuji.

Omamori – Good Luck Charms

Omamorialso known as good luck charms or amulets, derives from the Japanese word “mamoru” (守る), meaning to protect. These are small pieces of paper sealed inside a small embroidered pouch. Generally, they are for good luck and protection against bad luck. However, there are many different types of omamori for specific purposes. Furthermore, shrines or temples take pride in their omamori designs, so you can find different ones wherever you go! Omamori typically ranges from 500 yen to 1000 yen.

This is an omamori for good health.

Using the attached string, you can keep your omamori anywhere, from a pencil case and wallet to a key holder.

You can keep the omamori for as long as you want. In Japan, some people believe these should be renewed each year. The old omamori is disposed of at the shrine where it was purchased during hatsumode.

What is Ema for at Japanese Shrines

Finally, when walking around a shrine, you may find some small wooden plaques with wishes written on them. These are known as ema and are a Shinto custom, so you will only find them at shrines, with prices ranging from around 500 yen to 1000 yen.

You can pick up your ema at the shrine booth and write your wish with the given pen. Sometimes, one side has a piece of art related to the shrine or shrine’s deity. In other cases, both sides are blank, so it is custom, but not necessary, to write your name and address (as if your wish follows you home).

So that’s all for our guide on shrines and temples and their differences. This scratches the surface of such a deep tradition and culture, but it is enough to get you started and experience them fully! Let us know your favorite shrine or temple in Japan in the comments!